Matthew Daniel and Alex Cannon |

In a recent Axios interview, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei warned that AI could wipe out half of all entry-level white-collar jobs within the next five years. Junior tech, consulting, finance, marketing, law, and sales roles are all at risk of vanishing before companies even have a chance to figure out the repercussions of their decisions.

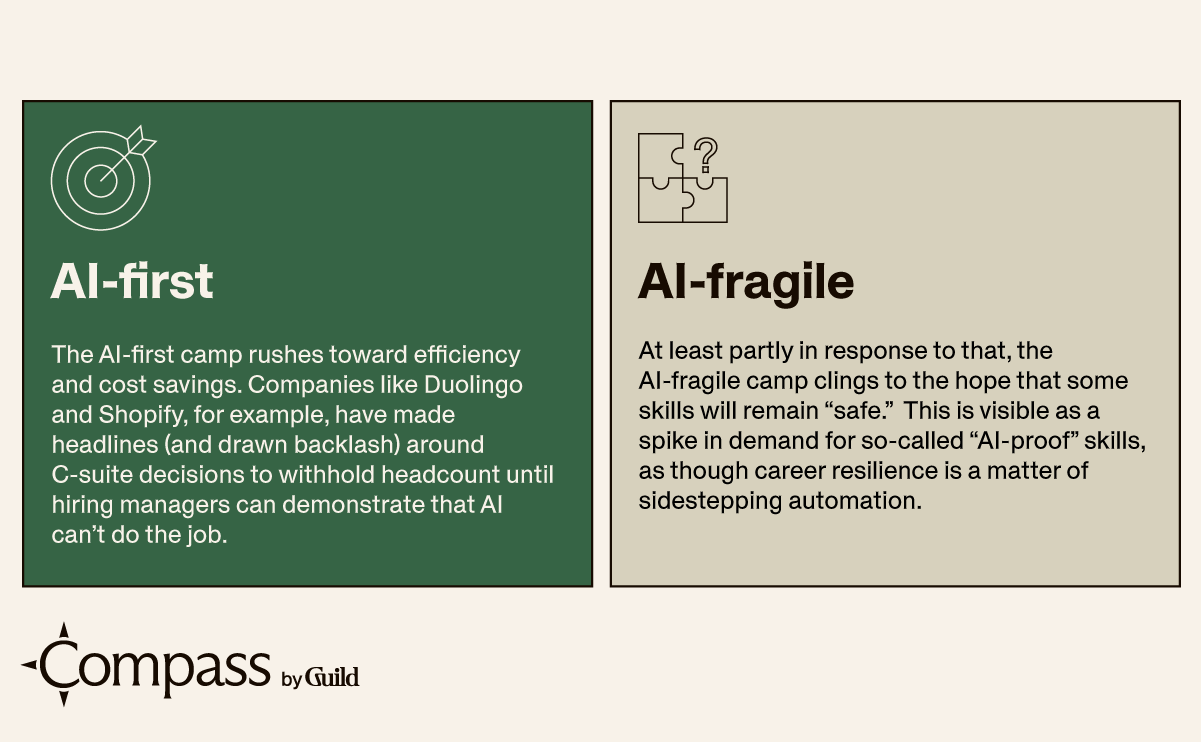

Whether or not that timeline is alarmist, the consensus among experts in the field is that AI stands to significantly transform the future of work, and companies need to prepare for that. Yet, so far, corporate thinking largely falls into one of two camps: AI-first and AI-fragile.

The problem with this thinking? Both miss the point. AI-first and AI-fragile both look at people in terms of the things they’re able to do that AI can’t. And both massively limit talent potential.

Stop designing around what AI can’t do.

Prioritizing automation ahead of human adaptation to automation can have the effect of shrinking your org chart and your organization’s potential. That approach means forgoing investment in judgment and sense-making in favor of repeatable tasks and speed — and in the process, builds a workforce that may be technically efficient but strategically hollow. Teams might resolve tickets faster, ship features more quickly, or generate content at scale — but without the judgment to spot churn risk, market shifts, or strategic misalignment, all that efficiency gained comes at the cost of foresight. Hyperfixating on what AI cannot do (yet) only ends in ceding more ground as advancements accelerate.

The skills we once labeled ‘safe’ from automation because they were emotional, expressive, or intuitive aren’t as untouchable as we once thought.

And when AI is used to replace, rather than augment, human capability, its potential is often undercut. Earlier this year, Swedish fintech company Klarna ended up rehiring customer-service representatives after conceding that automation alone fell short of the service-quality that customers expected. What looks like optimization in the short term can chip away at resilience in the long term. It’s the same kind of short-term thinking that gave us supply-chain and talent shortages coming out of Covid-19.

Case in point. Consider a manufacturer that fully automates frontline quality checks. The system might catch obvious errors and defects, but it could miss the early, more ambiguous signs that something is off — clues that an experienced operator would catch through context, history, and hard-to-replicate accumulated knowledge. That very human capability to interpret early signals (and connect the dots across functions and time) gets lost.

The result? What seems like efficiency turns into rigidity; what seems like progress at first becomes a brittle system with no give.

It also creates a dangerous false binary: either AI does the job or a human does. That mindset assumes there is no meaningful space in between: no collaboration, no mutual amplification, no need for new expertise because AI exists.

The space in between is where the future of work lives. And it’s time to rethink which skills actually prepare people to succeed there.

Most soft skills aren’t exclusively human anymore.

Let’s start with an uncomfortable truth: many of the skills once considered uniquely human … aren’t.

Within just a couple of years, assumptions about what only humans could do have been upended. AI can now act as a therapist, leveraging “empathy scripts” — responses generated to demonstrate care based on emotional cues it detects in user input. It can brainstorm product names and ads with surprising creativity and wit. It can write novel chapters, compose lo-fi beats, and plan events. The skills we once labeled “safe” from automation because they were emotional, expressive, or intuitive aren’t as untouchable as we thought.

What makes a skill durable in the age of AI isn’t about whether a machine can or can’t perform it. It’s now often about how a human can apply, adapt, and elevate it in tandem with AI.

And it’s not just soft skills. Even technical tools that held their ground for decades, like spreadsheet modeling in Excel, have been leapfrogged overnight by generative systems that can analyze, summarize, and visualize in a fraction of the time.

None of that makes the underlying skills obsolete. But it does challenge the assumptions we’ve been using to frame them.

What makes a skill durable in the age of AI isn’t about whether a machine can or can’t perform it. It’s now often about how a human can apply, adapt, and elevate it in tandem with AI.

The assumption about durable skills has always been that they would withstand disruption — economic cycles, technological innovation, even automation. The word durable reinforces that logic: it suggests stability. Insulation. Safety. But in this new context, that definition doesn’t hold. Durability can’t be about protection anymore. It must factor in amplification.

The problem is that many of the soft, or durable, skills topping job descriptions for high-demand roles — like communication, collaboration, critical thinking — are too broad and too vague to be useful with AI in the picture. Instead, maybe we should talk about directionally durable skills. One way to do that is to consider which capabilities grow more valuable because AI is in the loop.

Here are three examples:

Interpretative thinking

The ability to make sense of mixed signals. For example, understanding why a patient’s words don’t align with their behavior, or how a client’s polite feedback may mask deeper dissatisfaction.Contextual fluency

The skill of recognizing what matters in the moment, without needing to be briefed. This is especially valuable when urgency or efficiency is a factor, like catching a red flag in a meeting or knowing when a data-driven decision needs a human override.Situational ethics

The judgement to act when the rules don’t cleanly apply. This is less about compliance and more about discernment when the stakes are high and the answers aren’t obvious.

These skills come to life in the kinds of choices AI struggles with on its own, like knowing when a rewrite of a brand story will politically backfire, or understanding that after a RIF, an ostensibly neutral word like “realignment,” is suddenly high-voltage.

Discernment matters exponentially more now.

At the start of every durable skill is the same core human capability: discernment.

Discernment is the ability to read between the lines, to weigh context, timing, relationships, emotional subtext — all in service of not just processing information but interpreting it. Discernment means knowing when to override an obvious answer, when to pause before making a decision, or when a decision that seems right might be strategically unsound. Let's not pretend most folks new to the workforce have that when they arrive.

It’s also where AI consistently stumbles on its own. Not because it fails, but because it doesn’t know what it doesn’t know. In an AI-enabled workplace, discernment becomes the ability to make judgement calls in high-context, ambiguous situations in collaboration with AI systems.

An easy example of this is scheduling. AI can automate scheduling meetings at scale, but it can’t always sense when not to schedule a meeting: when someone has been laid off, for instance, or when a back-to-back string of meetings that are not unusual in length but stressful in nature can tip into burnout.

Language is another example. Large Language Models (LLMs) use a method called token weighting, which looks for tone and emphasis in language so the model can determine and mirror emotion. Though reliable, that method can miss quiet signals. A phrase like “I can’t do this anymore” might appear innocuous to an LLM. To a colleague with context, though, it may signal a cry for help.

And that is the key difference: AI scales pattern recognition but it cannot reliably scale situational awareness. Discernment is what emerges when humans notice what AI overlooks. It’s the difference between response and responsibility.

AI systems that don’t keep humans in the loop don’t strategically scale intelligence; they speed up decision-making with no accountability. Instead, when people are seen as critical to any strategic infrastructure — including AI adoption — organizations get workforces that don’t just adapt to change but direct it with discernment, insight, and purpose.

Durable skills evolve. That’s what makes them durable.

What we call a “durable” skill often reflects less about its intrinsic value and more about what society values at a given moment in history.

Take critical thinking. During the Industrial Revolution, critical thinking looked more like logical reasoning, mechanically and mathematically: optimizing assembly lines, calculating output rates, and sequencing labor processes. In the early 2000s, it looked more like structured problem-solving: decision trees, tradeoff matrices, and root cause analysis.

Today, in the age of AI, critical thinking means something different again:

Knowing when to override AI-generated outputs;

Evaluating not just accuracy but appropriateness; and nuance in sensitive or high-stakes contexts;

Evaluating whether an LLM output distorts, hallucinates, or invents data;

Identifying and challenging baked-in assumptions or detecting bias in training data;

And in the infamous catch-all: interpreting ambiguity.

This is still critical thinking; the context and stakes have changed, but not critical thinking itself. Instead, it’s been reframed for a more complex, generative, probabilistic world.

That’s the true nature of durability: it isn’t fixed. It’s reinterpreted and redeployed.

It’s also worth noting that most durable skills aren’t really single skills at all. They’re clusters of skills — competencies that flex to meet a given moment. For example, creativity can look like storytelling and design and strategy. Collaboration can mean working with peers and AI agents and systems. The label stays the same; it’s the practice that evolves.

For HR and L&D leaders, this is a challenge to not treat skills as artifacts, but as living, shifting capabilities. On paper, this is well-understood. Systemically, though, the tools used to classify and deploy skills often reduce flexible capabilities to fixed traits. Public taxonomies reflect this tension: in recent data from LinkedIn, high-demand skills include things like conflict mitigation and innovative thinking — capabilities that are deeply contextual and hard to pin down. Tagging 40,000 skills in a system designed to be machine-readable and job-matching-ready can flatten the expansiveness that makes durable skills valuable in the first place.

What this means for HR and L&D.

Without a broader vision, a defensive skilling approach to AI will backfire. It isn’t enough to ask what people need to learn before their jobs disappear. Practitioners have a responsibility to think beyond insulation and into complementarity; to design systems where humans and AI make each other more effective. What human capabilities become more valuable because AI exists?

Here are ways leaders can start doing that:

Build for discernment.

Traditional L&D approaches are often better suited for hard skills and compliance but not necessarily building up human judgement. Discernment — the ability to ask better questions, spot signals in noise, and apply judgement in ambiguity — is arguably the meta-skill of the AI era. Harvard Business Review even positions strong judgment as a core competitive advantage in AI-augmented systems.

Don’t wallow in the skills taxonomies of today.

The flexible and complex nature of durable skills presents an opportunity to stop pretending skills are entirely discrete and measurable. The skills that are most durable seem to resist easy labeling on a spreadsheet and maybe that’s part of the point: if taxonomies and job architectures treat them as discrete units, it’s worth examining if that flattens, rather than captures, value. Another problem: There are employees who are probably better off than they think from an AI-readiness perspective, but if skills taxonomies suggest something different, they may mistakenly go down the wrong learning path, which is costly for them and the organization. Durability will suddenly be redefined with new models.

Identify growth signals.

A skilling strategy that only reacts to what’s missing will miss the bigger opportunity. The question isn’t just “what do we need more of?” It’s “what strengths already exist in our workforce that become more valuable when AI enters the picture?” In that context, durable skills don’t just bridge gaps; they can change trajectories.

Make mobility strategic, not reactive.

During a time of succession panic and AI transformation, your most valuable people tend to be the most contextually aware: those with the insight to interpret complexity and the judgement to act on it. Make sure systems are designed to identify and elevate them.

Durable skills have never been fixed, and among those that matter most are human skills in relation to AI: interpretive, ethical, contextual, discerning. These are the capabilities that keep people in the loop, shape smart decisions, and guide responsible action under pressure. And they are foundational to a workforce that is not ready to just weather disruption, but to lead through it.